John Grisham (1955- ) was born in Jonesboro, Arkansas, the son of a construction worker. At the age of twelve, his family moved to Southaven, Mississippi. He graduated with a B.S. from Mississippi State University in 1979. He passed the Mississippi Bar exam in 1981, and received his J.D. from the University of Mississippi. In 1981, he married Renee Jones, with whom he had two children.

Grisham began a successful law practice in 1981, starting in criminal law, and moving to more lucrative civil law. In 1984, he was elected to the Mississippi State House of Representatives, a position he held in addition to running his law practice. A case he witnessed while in the state legislature led him to write his first novel, A Time to Kill (1989). He had trouble finding an agent and publisher. He eventually found both, and a limited run of 5,000 copies was printed of his first novel. In 1990, Grisham resigned from his position on state legislature and retired his practice. In 1991, Doubleday published his second novel, The Firm. It was a massive commercial success, as were his third and fourth novels, The Pelican Brief (1992) and The Client (1993). His fourth book, The Chamber (1994) is the first of eleven novels to become the number one annual bestselling novel in the U.S.

Since 1989, Grisham has published a total of 29 novels, five children's books, and a work of non-fiction. His family splits its time between homes in Oxford, Mississippi, Charlottesville, Virginia, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Grisham also serves as a board member on the Innocence Project.

Length: 435 pages

Subject/Genre: Last Wills and Testaments/Legal Thriller

The Testament is the most boring of the Grisham novels so far. The story begins in the first person, with elderly billionaire Troy Phelan preparing his last will and testament. The details are mildly interesting, but suffice it to say that he convinces his relatives (who he hates) that they'll be getting everything. He arranges the situation so he'll be declared sane by some of the best expert witnesses around, before jumping from the top floor of his skyscraper. Phelan's family and lawyer are surprised to discover that he has left everything to Rachel Lane, an illegitimate daughter no one knew about. To make matters worse, Rachel is a missionary living with a remote tribe somewhere in the Pantanal, a massive wetland region in South America. Phelan's lawyer tasks his recovering alcoholic colleague, Nate O'Riley, with finding the heiress. Also, this all takes place around Christmas, and Nate is repeatedly clear about his intense dislike of the holiday spirit.

Despite appearances, Grisham doesn't seem to own any tourism ventures in the Pantanal. Half the story focuses on how much O'Riley hates Christmas, loves alcohol, and just wants to make it out of the Pantanal alive. The other half focuses on just how scummy and vulturish Phelan's kids and grandkids are. This part would be more interesting if Phelan hadn't explained how his plan to make sure they got nothing worked, and this is a John Grisham novel: the bad guys never win, or at least not completely. So, half the time we're stuck with a pretty unsympathetic screw-up as he tries not to get eaten by alligators in a pseudo-adventure story, and the other half of the time we just hear about a clan of unsympathetic screw-ups as they try to carve off a piece of the estate of an unsympathetic billionaire. The people you're clearly supposed to be rooting for are annoying, the people you're supposed to hate are just exasperating, and it really just drifts aimlessly. By the time O'Riley finds Rachel you're as sick of the journey as he is, and then there's just another level of frustration when you find out [SPOILER]--- she doesn't want the goddamn money!

The Testament is the most boring of the Grisham novels so far. The story begins in the first person, with elderly billionaire Troy Phelan preparing his last will and testament. The details are mildly interesting, but suffice it to say that he convinces his relatives (who he hates) that they'll be getting everything. He arranges the situation so he'll be declared sane by some of the best expert witnesses around, before jumping from the top floor of his skyscraper. Phelan's family and lawyer are surprised to discover that he has left everything to Rachel Lane, an illegitimate daughter no one knew about. To make matters worse, Rachel is a missionary living with a remote tribe somewhere in the Pantanal, a massive wetland region in South America. Phelan's lawyer tasks his recovering alcoholic colleague, Nate O'Riley, with finding the heiress. Also, this all takes place around Christmas, and Nate is repeatedly clear about his intense dislike of the holiday spirit.

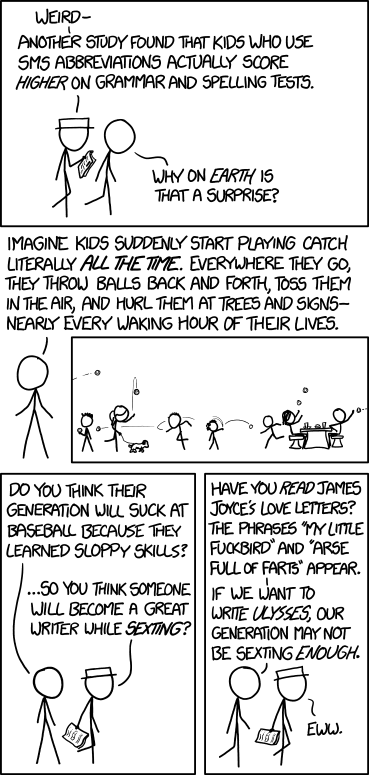

|

| Pictured: the real war on Christmas |

Despite appearances, Grisham doesn't seem to own any tourism ventures in the Pantanal. Half the story focuses on how much O'Riley hates Christmas, loves alcohol, and just wants to make it out of the Pantanal alive. The other half focuses on just how scummy and vulturish Phelan's kids and grandkids are. This part would be more interesting if Phelan hadn't explained how his plan to make sure they got nothing worked, and this is a John Grisham novel: the bad guys never win, or at least not completely. So, half the time we're stuck with a pretty unsympathetic screw-up as he tries not to get eaten by alligators in a pseudo-adventure story, and the other half of the time we just hear about a clan of unsympathetic screw-ups as they try to carve off a piece of the estate of an unsympathetic billionaire. The people you're clearly supposed to be rooting for are annoying, the people you're supposed to hate are just exasperating, and it really just drifts aimlessly. By the time O'Riley finds Rachel you're as sick of the journey as he is, and then there's just another level of frustration when you find out [SPOILER]--- she doesn't want the goddamn money!

This is an aimless, boring, and all around pointless novel.

Bestsellers of 1999:

1. The Testament by John Grisham

2. Hannibal by Thomas Harris

3. Assassins by Jerry B. Jenkins and Tim LaHaye

4. Star Wars: Episode 1, The Phantom Menace by Terry Brooks

5. Timeline by Michael Crichton

6. Hearts in Atlantis by Stephen King

7. Apollyon by Jerry B. Jenkins and Time LaHaye

8. The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon by Stephen King

9. Irresistible Forces by Danielle Steel

10. Tara Road by Maeve Binchy

Also Published in 1999:

The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem

Cryptonomicon by Neal Stephenson

Battle Royale by Koushun Takami